Posts Tagged ‘community organizing’

Why MoveOn Should Introduce Me to My Neighbors

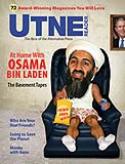

Recently, my dad proposed in his back-page column in the May/June Utne Reader, titled “An Open Letter to MoveOn,” that the nation’s premier progressive organization should go beyond issue-driven campaigns and “lead a community organizing movement across America.” (Yes, in case you’re wondering, my dad founded Utne Reader, and I worked there as a writer and editor for eight years.)

Recently, my dad proposed in his back-page column in the May/June Utne Reader, titled “An Open Letter to MoveOn,” that the nation’s premier progressive organization should go beyond issue-driven campaigns and “lead a community organizing movement across America.” (Yes, in case you’re wondering, my dad founded Utne Reader, and I worked there as a writer and editor for eight years.)

I couldn’t agree more. I especially like his suggestion that MoveOn stage a series of large revival-style cultural events designed to introduce members to each other:

MoveOn could kick off the movement by hosting stadium-sized events, harking back to 19th-century chautauquas and tent shows. Attendees would sit together according to particular affinities: parents of young children, schoolteachers, health care workers, clergy, small-business owners, elders. Like-minded participants could share their ideas about particular issues, like clean, green energy and single-payer health care. Or, if seating were assigned based on zip code and postal route, people would meet their neighbors in a positively charged environment.

All this would be interspersed with musical entertainment, stand-up polemic, and perhaps a Jumbotron visit from Obama himself. Consider it an extended-family/neighborhood reunion in which participants would meet some long-lost relatives for the very first time.

After the event, attendees would all receive lists of the 20 other participants who live closest to them. House parties would follow. Instead of discussing issues, we would simply get to know each other by telling each other our stories of “self, us, and now.”

(Telling stories of “self, us, and now” is a technique used in the Camp MoveOn organizer trainings, one of which my dad attended last year, and which inspired his column.)

I’d be thrilled to attend a rally of 5, 10 or 20 thousand MoveOn members in my area, knowing that I’d hear great bands and speakers and have a chance to meet and converse with other progressives in my neighborhood.

People often accuse MoveOn of mere “clicktivism,” of sapping the activist energies of grassroots progressives by calling on people to sign petition after petition on narrow issue campaigns. People either feel they can just click and be done with it, or they get tired of the incessant calls to action and tune out, the argument goes.

That argument is unfair. MoveOn has done more in the past decade than any other organization to build the American progressive movement, to give it a sense of identity and an outlet to flex its political muscle. The group has pioneered new models of online advocacy and fundraising, developing many of the tools and strategies that are now de rigeur in both issue and electoral campaigns across the political spectrum. Most importantly, MoveOn has experimented with new ways to move people from online to offline. Every person who signs a MoveOn petition is invited to take further action — write or call Congress, donate to the campaign, attend a rally, vigil or organizing meeting. MoveOn was largely responsible for mobilizing people to turn out on what became the largest global day of protest in history, the simultaneous anti-war rallies in hundreds of cities across the US and around the globe on the eve of the Iraq War in 2003. And if it weren’t for MoveOn paving the way, and providing critical early support, the presidential campaigns of both Howard Dean and Barack Obama might never have been possible.

Yet some criticism is justified. MoveOn’s sheer scale (5 million members) and obsession with numbers can make individual activists feel insignificant and campaigns feel impersonal.

As the de facto connective tissue of much of the progressive movement, MoveOn has an opportunity to go beyond issue campaigns and strengthen the movement by introducing its members to each other. Not under the rubric of any particular campaign or action. Simply connecting people to each other at the local level so they can start conversations and build community would be a powerful step toward revitalizing and re-engaging progressives, many of whom tuned out after pouring their hearts out to put Obama in the White House.

Introducing MoveOn members (like myself) to each other and inviting us to share stories of “self, us, and now,” and to start conversations about our hopes and dreams for our families, neighborhoods, country and planet could be the best way to inoculate the body politic against the cynicism and hatred emanating from the Tea Party, Congress, and the media. It would surely lead to more committed local activism, would surface new issues and ideas, and could rekindle the sense of hope and possibility that drove so many of us to pound the pavement and open our wallets for Obama in 2008. As my dad says: “This could be the start of an earthshaking nationwide movement.”

So how about it, MoveOn? Please introduce me to my neighbors.

The City as Community-Building Platform

[Cross-posted from the Zanby blog. -LU]

I recently helped facilitate Open Gov West, a two-day conference on “Gov 2.0” organized by my friend Sarah Schacht, executive director of Knowledge As Power. Over 200 open government advocates and practitioners came to Seattle City Hall from across the Pacific Northwest and Western Canada, plus a few from farther afield.

I recently helped facilitate Open Gov West, a two-day conference on “Gov 2.0” organized by my friend Sarah Schacht, executive director of Knowledge As Power. Over 200 open government advocates and practitioners came to Seattle City Hall from across the Pacific Northwest and Western Canada, plus a few from farther afield.

Day 1 was a traditional conference, with programmed panels, a keynote speaker, and “work sessions” where attendees came up with recommendations for action in the areas of open government policy; data and document standards; funding; and working with non-traditional partners. Day 2 was an unconference, where anyone could offer a session on any topic.

At a discussion session on Day 2 titled “The Architecture of Gov’t 2.0,” Vancouver-based facilitator and web strategist Gordon Ross posed a provocative question: “What would the city website of your dreams do?”

The City Website of My Dreams

I’ve been pondering that question for a long time. Here’s what I wish I had said in that session:

The city website of my dreams would not only let me find relevant information, process transactions, lodge complaints, and communicate with elected officials. It would help me connect with my neighbors.

When I move into a new neighborhood, I wish I could go to the city’s website and join a group for my block (or a collection of several blocks) — complete with discussions, event calendar, photos, videos, and listings of relevant city services, businesses, nonprofits, neighborhood associations, and so forth. That way I could plug in and get to know my neighborhood (and my neighbors) quicker than ever. I could browse archived discussions to see what issues have been on my neighbors’ minds, peruse photos and videos from recent block parties and festivals, and check the calendar for upcoming events. And if I moved to a new neighborhood, I could just quit the online group for my old neighborhood and join my new one, taking my profile, friends, and history with me.

Such a platform would give me and my neighbors a powerful tool to self-organize — everything from potlucks to crime-watch patrols, yard sales, childcare swaps, street cleanups and community meetings about city policies of interest to the neighborhood. We could organize car-, bike-, and tool-sharing coops. It would give us a quick way to share alerts about burglaries or fires.

And it would give the city a powerful way of targeting communications to specific blocks. Need to clear the street because of a snow emergency, tree-trimming, or a broken water main? Just send a message to that block’s listserve and word will spread fast. Add an SMS gateway to send text messages to residents’ mobile phones and word will spread even faster. Connect it all to a CRM database and an Open 311 system and you’ve got a powerful tool set for citizens to engage with the city not just as individuals, but as groups, as neighborhoods, as communities.

That’s the grand vision the old community organizer in me has for what a city website could do for citizen engagement.

Pieces of this vision already exist, mostly organized ad hoc on private platforms like Facebook, Google Groups, Ning, and all manner of blogs and email lists. There are a few organized, larger-scale examples. E-Democracy.org hosts email discussion lists for 25+ communities across the US, UK and New Zealand. Frankfurt Gestalten (“Create Frankfurt”), is a Drupal-based project inspired by the great pothole apps FixMyStreet (UK) and SeeClickFix (US), but with a greater emphasis on groups organizing around neighborhood initiatives proposed by users. The Dutch foundation Web in de Wijk (“Web in the Neighborhoods”) provides a toolkit for residents to create their own neighborhood websites. The explosion of hyperlocal news blogs — like WestSeattleBlog and MyBallard in Seattle — has proven that there’s a hunger for online spaces that support offline neighborhood-level community-building.

Of all the sites I’ve seen, Neighbors for Neighbors comes closest to the vision I describe above. This Boston-based nonprofit has built Ning networks for all 18 neighborhoods across the city, stitched together as a citywide network under an umbrella WordPress blog. City staff, neighborhood activists, landlords, business owners, police, and residents of all stripes are active on the site, using it to organize everything from potlucks to pickup soccer games to public meetings about saving neighborhood libraries.

But I have yet to see such a network of self-organizing hyper-local community groups fully integrated with a city’s website.

Zanby’s Groups-of-Groups Approach

I’d love to build a system like this on the Zanby platform. Our unique groups-of-groups architecture enables the clustering of local groups into “group families” around any criteria — like geography, of course, but also other affinities that might unite certain block groups to others in different parts of the city, like proximity to schools, libraries, parks, transit lines, waterfronts, commercial zones, etc. Those groups could easily network and collaborate with other groups across the city with shared interests by joining group families organized around those interests. This architecture allows groups to network with other groups.

Imagine, for example, that a block in Boston lies within earshot of a freeway, borders a river, has a transit stop on it and is home to many Spanish speakers. In addition to belonging to one of those 18 geographic neighborhood group families, my block could join families for, say, all the blocks across the city that lie along the same light-rail line, or along Boston Harbor and the Charles River, or along highways, or with similar demographics. Those groups might share certain interests and concerns with each other that don’t map to the geographic neighborhood lines.

Meanwhile, a group a few blocks away might not be so concerned about freeway noise or transit safety. But it has a community garden and a retirement home on it. That group might join group families organized around elderly issues and community gardens. The host of a Highway Neighbors group family could create events, discussions, documents, etc. that are easily shared with all of the groups in the family.

The key concept here is that group families allow groups to network and collaborate with other groups.

It’s also fairly easy to integrate third-party tools and data into a Zanby community, using APIs, RSS feeds and embeddable objects. So each block group and neighborhood group family could serve as a social media dashboard displaying discussions, events, documents, etc. generated by Zanby, side-by-side with feeds of info from city databases, video streams of public meetings, live chats with residents and city officials, etc.

The Other ‘L’ Word: Liability

Legal experts have raised concerns about liability when the government hosts open forums for civic dialogue. Government lawyers get nervous about being sued for censorship if, for example, an employee deletes a profane or racist comment on a city blog or message board. And if they don’t moderate such comments, they could be sued for facilitating hate speech. Similar liability concerns were common a decade ago in the private sector, mainly in the media industry, as newspaper and magazine publishers struggled with whether to add blogs, reader comments, and forums on their websites. Those issues have largely been sorted out.

Fortunately, while the public sector may be a few years behind in sorting out these issues, it appears to be catching up fast. In the past year, 24 federal agencies, and many city and state governments, have used IdeaScale and similar apps to create open forums for sourcing ideas from the public. The website of the New York State Senate, a model of open government, now hosts blogs for every senator, including public comments, and allows the public to post comments on bills. The White House also recently published new guidelines for federal employees on how to use social media to engage the public.

Helping Communities Help Themselves

Just like social media is reshaping whole industries by slashing the transaction costs of engagement, it holds tremendous potential to reshape government — or more importantly, the relationship between citizens and government. There was much talk at the Open Gov West conference about how governments at all levels can use social media and online communities to engage citizens in dialogue, to leverage their knowledge, skills, passions, and willingness to volunteer their time and energy to solve public problems and improve their communities.

But as Doug Schuler, of the Public Sphere Project, argued, “We shouldn’t be talking about how government can leverage citizens. We should be talking about how citizens can leverage the government.” After all, the government is there to serve the people, not the other way around, right?

Yes, and to that end the government should be a vehicle for helping people help themselves — not just as individuals, but as communities, providing the social space for civic spirit to grow. I believe that putting tools in the hands of citizens to self-organize and build community — through the government website — is one powerful way to do that. Vibrant civic life requires infrastructure. I hope that one day it’s considered as normal, and vital, for city governments to provide such community infrastructure online as it is to build and maintain parks and town squares offline.